Note: This article was first published on the UK in a Changing Europe blog.

Brexit extended the reach of the UK’s borders into the lives of EU citizens, the majority of whom had previously enjoyed a lack of scrutiny of their rights to live and work in the UK. For British citizens, the loss of EU citizenship through Brexit means losing the rights to freedom of movement. But how has this been experienced by those directly impacted, such as members of migrant families in the UK and EU?

We focus here on one aspect of this question. The experiences of Brexit re-bordering within the space of intimate relationships. This includes those in mixed-status families, where migration and/or citizenship statuses vary between, for example, partners, parents and children.

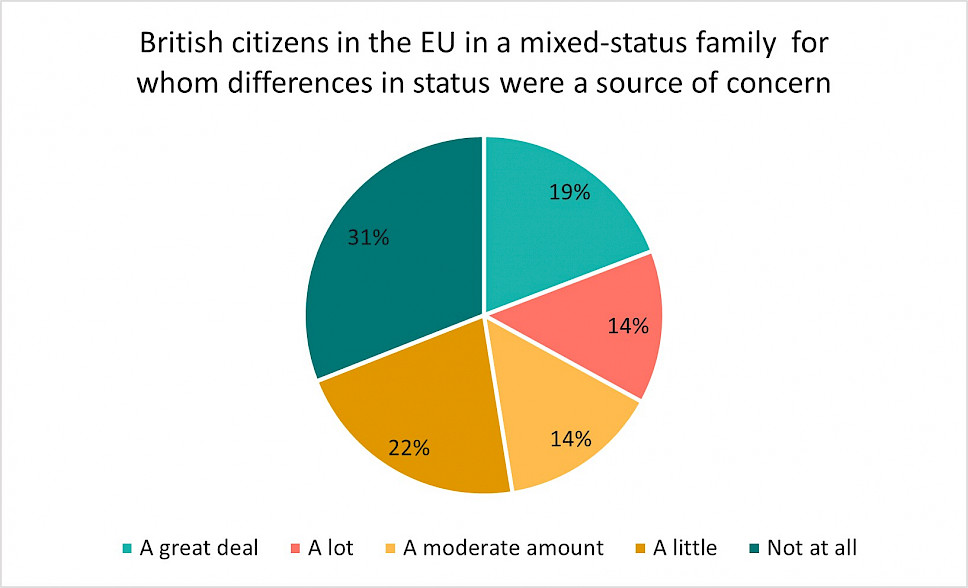

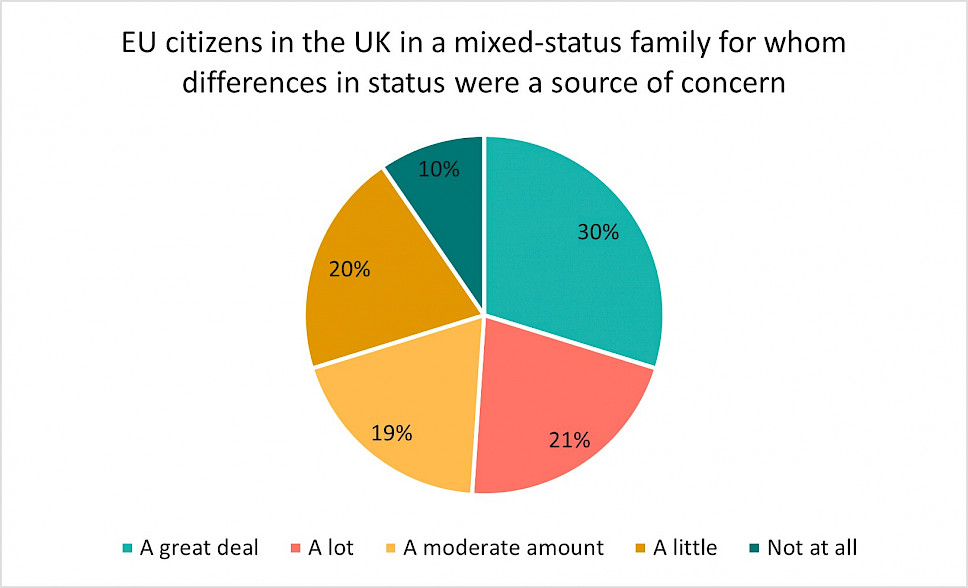

As part of the survey ‘Migration and Citizenship after Brexit’, we conducted for the MIGZEN research project, we asked EU citizens in the UK and British citizens in the EU whether differences in citizenship and/or migration status among close family members had been an issue of concern since Brexit. The graphs below show that, for a large share of those responding, it definitely has:

In this blog we examine the shapes that these concerns have taken. We start by providing a brief overview of the new legal landscape such mixed-status families find themselves in.

Family migrations before and after Brexit

Under EU law, freedom of movement extends to EU citizens’ qualifying family members, irrespective of their nationality. They can conduct their family life in their country of choice, whilst retaining the flexibility to move in, out and onwards. The exercise of Freedom of Movement further enables EU citizens to overcome restrictive domestic family reunion laws and policies via the so-called Surinder Singh route.

For EU citizens in the UK and British citizens, there have been significant changes for who can access these rights and on what terms. The Withdrawal Agreement protects the family reunion rights of settled or pre-settled EU citizens in the UK, and British citizens who were living in an EU Member State since before 1 January 2021. For a limited time period, the EU law-based family reunion rights of British citizens returning to the UK from the EU were also preserved; however, this possibility came to a close on 29 March 2022 (unless reasonable grounds for belated applications persist). But for others – ‘new’ EU migrants in the UK, British migrants in the EU, and UK repatriates – domestic immigration laws and policies apply.

Whilst this division of rights and border regimes may look neat and clear-cut, the realities that these populations navigate are far more complex, uncertain, and precarious. This is particularly evident in the context of mixed-status families.

Bordering intimacies

The findings of our survey ‘Migration and Citizenship after Brexit’ shows some of the many ways in which Brexit has brought borders into the space of these mixed-status relationships and the lives of migrant families. As our recent research brief ‘British citizens in the EU after Brexit’ shows, this was particularly pronounced for British-European families living in the EU/EEA.

For some respondents, Brexit has created a fissure within their family sphere, engendering negative emotions such as a sense of being ‘different’, or at risk of drifting apart from each other:

Just don’t feel I belong to the same [family] nucleus anymore. (EU citizen in the UK)

Having a precarious status in [the EU country of residence] in the post referendum period has been a psychological strain on me and on my children, who were concerned about what might happen to me in the future. (British citizen in the EU)

Competing family loyalties may take the shape of intergenerational trade-offs. Such is for example the case for parents having to choose between staying put to secure their children’s rights and opportunities in the country of residence and returning to their country of origin to care for their elderly:

We would have moved back to the UK to be closer to grandparents if our children had had the right to return to [their current EU country of residence] (for work/apply for jobs here) in the future as they would have done before Brexit. (British citizen in the EU)

What becomes clear is how intimate relations cross borders and borders cross intimate relations, including how these make, fracture, and reconstitute these ties:

My partner and I want to settle in Italy but he is extra-EU. He now got British citizenship, but it came at a time where this is basically useless to move to the EU. This will likely affect our marriage plans, although we do not really believe in marriage. (EU citizen in the UK)

Brexit-borne family concerns were often narrated in relation to the urge and complexity of getting the right papers to be allowed to conduct one’s intimate relationships as intended:

We had to make sure that Brexit (and loss of EU citizenship rights) did not interfere with our relationship. Therefore, I went through the process to register as a resident under the Withdrawal Agreement. (British citizen in the EU)

But realising these ambitions is also not equally accessible. Nor are its stakes equal. From the costs of acquiring these papers to the dependence of immigration status on the subsistence of an intimate relation, there is the potential for new vulnerabilities to emerge from these fractured intimacies:

My wife is a Russian citizen. Her residency and right to live and work depend upon my status under article 18 of the Withdrawal Agreement. The uncertainty delayed moving and even now, she fears a potential move to [another EU country] as her residency rights are totally dependent upon those of me. (British citizen in the EU)

Generational reverberations

The effects of the Brexit-driven rigidities and fissures on the family lives of EU and British citizens are just beginning to unravel. What is clear is that they are here to stay. Within the space of intimate relations, the differentiation of rights to mobility and settlement proliferates. And with effects that will be felt across generations as the borders between the UK and EU harden.

By Elena Zambelli, Michaela Benson and Nando Sigona from the Rebordering Britain and Britons after Brexit project.

Image credit: Photo by Elena Zambelli

To cite this blog:

Zambelli, E., Benson, M., and Sigona, N.(2022) How Brexit transformed mobile families into migrant families. UK in a Changing Europe, 5 May 2022. [Available Online at: https://ukandeu.ac.uk/how-brexit-transformed-mobile-families-into-migrant-families/]