What can English-language testing for the purposes of immigration and citizenship tell us about who counts as British today?

Michaela Benson [MB]: Welcome to “Who do we think we are?”, a podcast exploring some of the forgotten stories of British citizenship. I am your host, Michaela Benson, a sociologist specialising in citizenship, migration and belonging, and professor in public sociology at Lancaster University. Join me over the course of the series as I debunk the taken-for-granted understandings of citizenship and explore how thinking differently about citizenship helps us to make sense of some of the most pressing issues of our times.

Kamran Khan [KK]: […] When kind of the borders of the United Kingdom, you know, expand through conquest and colonialism, and English is at the forefront of that, you know. That's why for example, in India they speak, you know, English arrived there, right? Then what we see is that the kind of retreat into a nation, then those borders get pulled back, and now it's about, well, who can we exclude? Who can we include? Who belongs and who doesn't? So you see, actually, maybe we need to think less about language tests as kinds of educational tests only, but in terms of bordering.

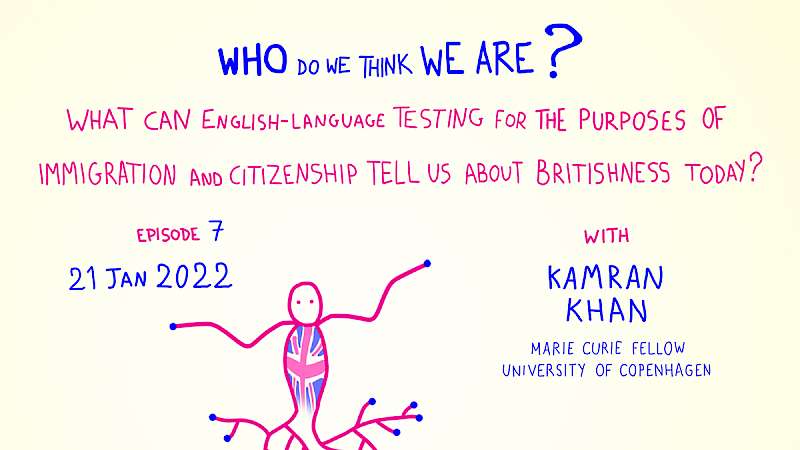

MB: That was my guest in today's episode, Kamran Khan, talking about how English was at the heart of the British Empire's project of colonisation, and remains part of the process of deciding who is and isn't allowed to enter and settle in the UK today. Kamran is a Marie Curie fellow at the University of Copenhagen, researching language and security. He's also a member of the IdentiCat research group at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya and Barcelona, where he was previously a postdoctoral fellow.

We've talked a lot on the series so far about changes in Britain's Immigration and Nationality legislation from the 1960s until the British Nationality Act 1981. And we've looked in-depth at some of the racialised injustices produced through these changes that laid the foundation for the UK’s current immigration regime; from the Windrush deportation scandal with Elsa Oommen in Episode Three (#3), to the removal of birthright citizenship from those born in the UK in our conversation with Imogen Tyler in Episode Four (#4). But a lot has happened since the BNA 1981, which is after all, as old as I am.

We're going to look at some of this today with a particular focus on the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act of 2002, and how this was caught up in the increasing global securitisation of borders, following the events of 9/11. We'll be hearing more from Kamran about the domestic context in the UK that shaped the introduction of language testing for those seeking to enter the UK and become citizens. We'll be discussing the politics of language testing in the context of rising Islamophobia. And we'll be thinking through the relationship between language and citizenship, and what this helps to make visible about Britishness and belonging.

But first, we're going to hear from George about his experiences of language testing. When George and I were talking about the plans for this episode, he told me about his own experiences of English Language Testing. He needed to do this in order to be accepted for his Master’s programme in London. And, as he makes clear, it was anything but plain sailing.

George Kalivis [GK]: So, reading this made me think again about my own experiences of completing English tests, in order to demonstrate that I met the minimum requirements to be accepted onto a Master's degree in England. Being confident of my skills in English, which I had been studying since childhood, and already using extensively in my everyday professional and academic life, I briefly went through the format of the British Council’s IELTS test a couple of days before taking it for the first time in 2019.

The Listening and Reading sections of the test were basically a series of digital quizzes. I even had finished the reading part 15 minutes earlier than the given time. The Writing, however, wasn't a quiz. It was some kind of time-technical performance that had little to do with actual expressive and skilful writing. People around me started typing in their keyboards really fast, creating an unprecedented noise in the room. What were they writing? When did they even get the time to plan their text? Had they already memorised standard text responses, which they were then quickly typing in the screen? Yes, they had! And yes, this was not at all about proving any writing skills. It was a race.

In my case, I never got the chance to finish my writing as I run out of time, and my text did not include any of the IELTS standardised phrases. While my overall score was quite above what was required for my studies, my writing score was below the 6.5 marks I needed for an unconditional offer. I emailed and called the Admissions Office at the university, obviously in English, assuring them that my language skills were good enough for attending the course, and to request whether they could make an exception and consider my IELTS results as enough proof of my language skills. Unfortunately, they then informed me that I hadn't met my English requirements, and therefore I had to retake the test, which I did. This time, finishing the writing part within the designated time.

My results of writing remained the same. With just a few weeks away from the commence of the academic term, I found myself being deeply stressed, frustrated and disappointed. Out of options, I emailed one of my course’s convenors at Goldsmiths, again, assuring her about my English language skills, attaching some texts of mine in English, stating that I was willing to do anything needed to further prove or improve my English skills once in London, and asking for my future at the university not to be determined by a problematic technical examination of my language skills that only led to contrasting results, which were irrelevant to my true skills. Thankfully, the course convenor understood. Having now completed my MA with distinction, I am currently carrying out my PhD research in the Department of Sociology at Goldsmiths. It worked out for me, but would it work out for everyone?

MB: George's experiences of the test made me think about what is really tested for in English language testing. And how is this related to the process where English became and has remained a “world language”? I think about the fact that my mother took a conscious decision when I was a baby not to teach me Cantonese. What does it say that she described this, half-jokingly admittedly, as a “useless language”? Despite it being the primary language through which she communicated with her own mother. But I also think about how, despite years of learning French in school and getting top marks, when I moved to France to do the research for my PhD in the early 2000s, I struggled to speak in French. And while it improved over the time I was there, once I returned to the UK it deteriorated again. So when I went back to do research in the aftermath of Brexit, over a decade later, I felt I was back at step one. And yet, my Greek-born husband lives his everyday life in two languages, speaking Greek with his family, while English is the language of our home-life, and his working life.

But more than anything, my conversations about English language with George, Kamran, and previously with Anne-Marie Fortier, my guests in Episode Five (#5), left me questioning the politics of language testing. What is really being judged in this process? And what does this tell us about the shape of Britishness and belonging?

My starting point in thinking through this is that English language testing was only very recently introduced into the process of naturalisation. That is the process by which people who hold other citizenships that are settled in the UK can apply to become British citizens. While the foundations of English language testing had been laid down in the British Nationality Act of 1981, in reality, they'd rarely been implemented. That is, until the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act of 2002. The Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act was a major piece of legislation brought into effect by the new Labour Government. Among other things, it brought in provisions for the establishment of so-called “accommodation centres” for those seeking asylum in the UK, and new provisions for detention and removal. But it's the first set of provisions, the ones that relate to nationality legislation, that I want to highlight here.

The Act addressed some of the remaining gender-based discrimination in nationality law so that the overseas-born children of British mothers, born between 1961 and 1981, could be entitled to registration as British citizens. It also updated provisions relating to the deprivation of citizenship, to make clear that British nationals holding any citizenship status, whether a citizen or, for example, a British Overseas citizen, could be deprived of their status by the Home Secretary, provided, they would not be made stateless in the process. As we’ll hear in a future episode, framed in this way, citizenship deprivation would disproportionately impact racially minoritised Britons. It also made clear that those with a connection to Hong Kong could not register as British Overseas Territory citizens, which, given provisions later brought in through the British Overseas Territory Act, would exclude the people of Hong Kong from a route to fall British citizenship.

To be clear, this was wide-reaching reform, which, while reducing further gender-based discrimination in nationality legislation, set in motion new requirements for those seeking to naturalise, making it harder, and extending provisions for citizenship deprivation, with consequences for current day legislation. It also made fundamental changes to the process of naturalization, extending the citizenship testing regime through the introduction of the “Life in the UK Test”, extending language testing requirements and making the citizenship ceremony a compulsory element of this process.

Before we go any further, I want to head back into the archive with George. He's been looking at how the Home Secretary of the time, David Blunkett, explained the new Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act.

GK: On the 15th of September, a few months before the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 received Royal Assent, the Guardian published an essay by the then Home Secretary, David Blunkett, entitled “What does citizenship mean today?”. In his text, Blunkett states that, and I quote: “Unless properly managed […] migration can be perceived as a threat to community stability and good race relations. Where asylum is used as a route to economic migration, it can cause deep resentment in the host community. Democratic governments need to ensure that their electorates have confidence and trust in the nationality, immigration and asylum systems they are operating, or people will turn to extremists for answers.”

Blunkett then continues to link this position to the broader political debates of the time, stating: “[…] the defence of our democratic way of life […] requires that the threat to security at home is met. Securing basic social order, and protecting people against attack, is a basic function of government […]. This is why, in the aftermath of 11 September, I took the Anti-Terrorism, Crime and Security Act through Parliament. I had to ensure that basic civil liberties and human rights were protected, at the same time as ensuring the protection of the public from terrorist attack in conditions of heightened threat.”

Later in his essay, Blunkett returns to discussing migration and citizenship legislation as a means for preventing both security and politically extremist threats; and right before concluding, he points out how, in his view, a successful form of citizenship should be highly related to new migrants' ability to speak English, outside and inside their houses, claiming: “[…] speaking English enables parents to converse with their children in English, as well as in their historic mother tongue, at home and to participate in wider modern culture. It helps overcome the schizophrenia which bedevils generational relationships. In as many as 30% of Asian British households, according to the recent citizenship survey, English is not spoken at home.” This piece of legislation received severe criticism at the time, from MPs, to UK- and US-based academics, as well as humanitarian organisations.

MB: I was just starting my PhD when this Act passed Royal Assent. The year before I'd watched live as the planes flew into the Twin Towers. On the surface, this new legislation was caught up in a broader political agenda framed around community cohesion and integration, which lay at the heart of ambitions for multicultural Britain. But listening back to the words now, nearly 20 years on, it's clear that this was a shift. It was the moment when national security became a significant feature of immigration and nationality legislation. And what's notable is that this placed increased scrutiny on British Muslim communities. We'll be hearing more about this from Kamran shortly. But I started our conversation by asking him about the backstory to the emergence of language testing.

KK: Probably the best way to look at it is kind of what happened before the test. In as much as, you know, we've had generations, you know, many immigrants who've come to the UK and survived without a test and, you know, made lives themselves. I think what's really interesting in comparing the British Nationality Act in ‘81, which is when the kind of language requirement kind of first came into kind of being. It was rarely used back then. So, there was no kind of standard test since 2004, and through the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act, we've had a test. So basically, until the test, it was assumed that you could function in society, and you can contribute in that way. I think what's happened since then, is that there's this kind of suspicion that until you demonstrate that you can, we won't believe you really can. And so you need that certificate. So, that's kind of one aspect of it. What that comes down to in the end is: Do you think a precondition for access to rights, and all those things that go with citizenship; should language be a precondition for that? And that comes, you know, is how you see the nation, you know, monolingualism and English is, is really tied up with the kind of idea of nation-building.

MB: So really, what you're saying then is that, you know, we should actually question what the political function of introducing language testing is, given that it's such a recent imposition into our kind of naturalisation regime, that kind of the way in which people become citizens, and to ask questions about, you know, that might also link, I suppose, to the kind of levels at which people are tested. But I really like this framing of you know, “do we really?”, you know: Should it be a given that language is a precondition for people's access to rights? And I think that's where, as soon as you start to look outside of the nation, that starts to get quite tricky, because, of course, you know, there are a set of human rights. There's all sorts of other things that, you know, we could say are something that we stand by, their kind of values. And yet, what's happening in a lot of settings, and the UK is not the only place where this happens, is that, in order for people to be able to access the rights of citizens, the protections of the state to its citizens, they're being told: “Oh, well, is your English good enough?”

KK: Yeah. And even kind of deeper within that, for example, is… it's as though multilingualism has no function in society. And yet most migrants who come to the UK, particularly if, you know, at that point, their English is maybe not so high at that moment, multilingualism works really well for them, because they need that kind of foundation. And within kind of linguistic, Applied Linguistics, there's this kind of idea of language ideologies. And so quite often, what you'll see is, if you think that languages of immigrants is problematic, quite often, that means, by definition, that they are problematic, the speakers are also problematic. And so that's kind of the heart of it as well, we see kind of any seat in general, and maybe we can talk about it later, but this kind of growing intolerance of other languages within British faces, which is at the same time, a kind of this kind of growing insularity as well.

MB: Yeah, I mean, I think that there's that famous situation of a woman wearing a hijab, sitting on the bus, speaking on the phone in another language, and she gets told to speak in English, and she said: “But I'm speaking Welsh.” You know, I think that points to some of the things that you're highlighting.

KK: Yeah. And, again, when we talk ideologically, that completely points to the dominance of Englishness within Britishness, right?

MB: When we start to look at language testing, I think it would be really interesting for people to hear a little bit more about where, when, and in what circumstances language testing is used in broader society in the UK?

KK: Yeah, so and English is probably the biggest kind of role of language going, it's the kind of biggest industry in terms of language teaching. So, quite often language testing is used obviously, for your kind of GCSE, you know, people who can learn a language until GCSE A-level; also for study abroad a lot, for international students who come to the UK. So there's this kind of whole set of exams and the different kinds of administrators that has a particular value in other countries, where, you know, English is seen as this kind of symbol of prestige. So, those are the kind of more… most kind of well known traditional ways university entrance, as well as a big one, all the universities. And they ask for something like an IELTS score, which is for people in higher education you'll be familiar with. And then we get into where it gets even trickier really, is for immigration purposes, and there's different ways that will happen. Citizenship Test is one example. We'll be into about other examples afterwards. But that kind of helps you situate this kind of broad kinds of differences between kind of international mobility, prestige, and the concerns of immigrants.

MB: So, it's quite widespread, is the point, and as you've already pointed out, it’s widespread both geographically and also in terms of what it's used for. So from, you know, the educational purposes, which is, I think, where it probably originated, and then kind of spreading out from that into all of these other aspects of life, to be used in citizenship testing. And I also think that I'm right about this, it’s also a precondition for some immigration into the UK. So people are tested before they are eligible for a visa, is that right?

KK: Yeah, so that would be, like family spouse reunification, for example. And that's actually, you know, if you follow the way testing is kind of spread, and kind of been implemented, you know, that's been the next step from citizenship, you know, it's… basically you need to take a test in an approved centre, if you're from outside of the European Union. Again, what countries would those be? You know, and if it's from a non-English speaking dominant kind of country, you need to take a test before you come into the UK. So, if we think of those as borders, then what we see is that the kind of the British border, then, is kind of externalised beyond our own territories. And if you look at the wider picture of that, it's this common thread of keeping mobility, as far away as possible for as long as possible, with, you know, and in all of those kinds of iterations. So it's not by coincidence, for example, that that's affected language testing.

MB: What I don't have a sense of is how idiosyncratic it is, in the UK? I mean, other places that do this? And, you know, is it similar? Or is it different? What's the…?

KK: Yeah, so this is the way you can see how kind of hopeless it is, you know, not that many countries had these types of tests before, but then kind of once one goes for it, then other countries look at that as kind of good practice. What you have then is that each country has its own kind of flavour within it. So the Spanish one, for example, nobody really asked for a test here; we've documented this and there wasn't much demand. But they went ahead and did a test because, you know, frankly, that's what other countries, you know, sort of big countries do as well, right? So, and since we kind of… since we all kind of have the “same problem” with the “same people”, then we kind of justified it in our methods.

How many times in the UK have we said an Australian style… You can finish the sentence, right? Whatever it is, it related to immigration. And so we pull on what's happening over there. And then we do the same. Likewise, in Australia, sometimes, you know, after the 2005 London bombings, and they had their own kind of riots, that criminal beach in Sydney. You know, this idea that: “Okay, we need to do something about a problematic community.” So it's probably best, okay, they do have their own, you know, they'll have their own levels, which kind of don't really make sense in a lot of ways, because there's different levels, different countries with different meanings, but what actually pretty makes sense is actually what brings them all together, and how do they all kind of interact with each other.

MB: I think we've raised a few really important points there. And I suppose the one that I really wanted to pick up on was this kind of relationship with I suppose key events and the kind of shifts in requirements off the back of those key events. As from my memory that 9/11 was a really significant turning point for questions around citizenship, and also the kind of increased interest in thinking about ways in which we could test people.

KK: Yeah. So probably the key point for British citizenship language testing then is 2001. And for anyone who remembers we had riots in three northern cities in the UK. And that was kind of between British Asian Pakistanis and far-right extremists at that time. And it kind of escalated and kind of was like carnage, basically. And the key kind of thing that came out in some of the reports afterwards was that there'd been this kind of tension that been building, and that tension was because people spoke different, lead parallel lives. That was the 10 Councils Commissioner[GK6] . So, the idea was that people were separate because they didn't all speak the same language. So that kind of blame was on migrant communities for not speaking English. And that led to a kind of tension. And okay, if that's the problem, the solution is to have something that brings everyone together. And that would be through citizenship, and that would be through language. And so that happened a few weeks before 9/11. And then you have 9/11; that happens, and then, you know, I don't know how well everyone remembers it, but you know, at that time, we had a very pre-emptive logic that came into things that we have to deal with things before they become a problem and stuff. So, you know, while it's not kind of, you know, directly related, it certainly adds its kind of flavour that, okay, so what we need to do is make sure they speak in English before there's any problems, and that solves a lot of things.

MB: So basically, what they were saying was, if these people only spoke English, then we wouldn't have these problems.

KK: Yeah, basically.

MB: I never really simplest…

KK: Even though most of the people involved in the riots were probably British-born anyways, but… It’s quite interesting, you know, that's actually what they thought would be the solution. And then obviously, then, you know, it's kind of a self-fulfilling prophecy afterwards. Because whenever kind of, you know, at that time, you know, the focus is Muslim communities, whenever something happens, then you go back to the citizenship: “Well, we have to make them even more integrated.” And that's clearly not, you know… “we need more measures”, and things like that. So, so that's kind of, that's probably the key moment, really, and then it kind of, you know, it kind of builds on itself after that.

MB: Before we close, I wanted to kind of draw out a little bit more. Your ideas about how citizenship and language are kind of caught up in securitization, because that's your real area of specialism really… To your mind, how do you think that this understanding of citizenship that draws in securitisation can help us to challenge more taken-for-granted understandings of citizenship?

KK: If we just use that example of the 2001 riots, you know; if language is the response to violence, what you're saying is that, you know, it's now on the table that language is this kind of inoculation to potential problems, but some particular “suspect problematic community”. And we see that getting picked up in various ways over the last 15 to 20 years. So, in 2011, for example, David Cameron gave kind of a famous speech, because that's where he said multilingualism is, has failed, yeah, we need, we need new approaches. Again, another example of something that was kind of, you know, really, on the fringes before, very significantly mainstream. And within that speech, at the security conference, he talked about these kinds of different problems by terrorism. And he talked about, you know, the language proficiency at that point, right? So if you frame all of those things together, you're saying that that's part of the problem. And then what we see over time as well is a kind of logic that gets revisited within counter-extremism. For example, if people don't speak very good English, they're vulnerable, and if they're vulnerable, they can be radicalised.

MB: English becomes a “protector” against people… of people?

KK: Exactly, yes. because if you can speak English, then you know, that, you know, the kind of ideas that you're being exposed to. That's the way in which, you know, something that's actually fairly educational, has now become this kind of defence within security discourses. And one of the things then, I mean, that feeds into, again, this kind of the idea of language linked to nation-building. And this is what makes us us, and citizenship comes into it because for both integration and security, active citizenship is seen as a kind of repellent or kind of defence against all of that. So, they've become quite interlinked. All of that going on with the kind of growing intolerance to other languages as well. Ranging from hate crimes of people who can be for not speaking a language, to kind of translation services being cut. So, it doesn't seem like they all fit, but actually, it does all fit because, you know, it's considered that a monolingual nation is a safe nation.

MB: I really like the way that Kamran draws out how language testing for the purposes of determining whether people could migrate to the UK and become citizens did not emerge in a vacuum. He clearly outlines the politics to this. That is sometimes, I think, concealed from view, in the notion that it's common sense that speaking English would be a measure of integration. You can take a look at today's episode notes for links to further resources on these topics, including to Kamran’s work on the relationship between language, citizenship and the securitisation of Britain's borders.

Thinking through the relationship between language and citizenship with Kamran, and with Anne-Marie Fortier in Episode Five (#5), has made me reflect again on my mother's decision that she would not insist that her children learn and speak Cantonese. At one stage, my younger brother and I were taught a little bit of Mandarin, and if I pushed, I could probably just about count to 10. But more seriously, I think that the decision my mother took, while a personal one makes more sense in the context of the pending shifts in Hong Kong's position in the world at that time, and the future signification of Hong Kong. Very simply, it was unclear what value Cantonese would have going forwards.

As the political scientist Benedict Anderson explains in Imagined Communities, a book that is one of the key texts in understanding nationalism, language plays a key role in the development of national identities. Some of you might be familiar with the ways in which states impose dominant languages, and what these do to those who speak minority languages, including what it does to their sense of identity and belonging. And a few examples that quickly sprang to mind are a Welsh in the UK case, or Catalan and Spain. But of course, there are many, many other cases. Indeed, the suppression of minority languages was one of the key ways in which nations were forged. I think we need to ask ourselves what it tells us about Britishness today, that so much weight is placed on the ability to speak English within the immigration regime and citizenship testing?

You’ve been listening to Who do we think we are? A podcast series produced and presented by me, Michaela Benson, as part of the British Academy funded mid-career fellowship Britain its overseas citizens.

The series was produced with the help of Emma Houlton and Andy Proctor at Art of Podcast

Archival research for the series and cover art by George Kalivis

If you like what you’ve heard, follow and rate us on your preferred podcast platform.

You can also find us at whodowethinkweare.org

And get in touch with us on twitter, Facebook and Instagram @AbtCitizenship

[End of transcript]

Should the ability to speak English be a precondition for access to rights and belonging in Britain today? What is really tested for in English-language testing for the purposes of migration and naturalisation? How is this connected to the global dominance of English as a ‘world language’? And what links this to the increasing hostility experienced by those speaking languages other than English in public space in Britain today? It might seem common sense that to live in a country you should be able to speak the language. But looking at the relatively short history of language testing into the UK’s citizenship testing regime reveals that not all is as it seems.

In this episode, we discuss how language testing was introduced into the naturalisation process alongside the Life in the UK test in 2002. What can the back story to its introduction tell us about Britishness and belonging? Presenter Michaela Benson outlines how the stage was set for English language ability to be part of the criteria for becoming British through the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. We hear from George about his experiences of language testing for the purposes of coming to the UK for postgraduate study and heads back into the archives to uncover how these new provisions related to anti-terrorism legislation. And we’re joined by sociolinguistics scholar Kamran Khan to explore how testing potential citizens for linguistic proficiency emerged against the backdrop of domestic concerns about integration and community cohesion and the global rise of Islamophobia in the wake of 9/11, and what this meant for Britishness and belonging.

In this episode we cover …

- Nationality Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 and 9/11

- Islamophobia and Britishness

- The relationship between language and nation-building

Quote

What that comes down to in the end is do you think language is a precondition for access to rights nd all those things that go with citizenship? And that comes with how you see the nation. Monolingualism and English is, is really tied up with the kind of idea of nation building.

— Kamran Khan

Where can you find out more about the topics in today’s episode?

Kamran tweets about his work (and other things) @securityling

His book Becoming a citizen explores many of the themes we address in the episode brought to life through the experiences of W, a Yemeni migrant in the UK, going through this process. But we also recommend his recent piece in Ethnicities that explores his ideas about the racial politics of language proficiency in the UK’s citizenship regime.

And we are recommending Nisha Kapoor’s fantastic book Deport, Deprive Extradite.

Call to action

Follow the podcast on all major podcasting platforms or through our RSS Feed.

To find out more about Who do we think we are?, including news, events and resources, follow us on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook.