Why we need to look at history to understand British citizenship today?

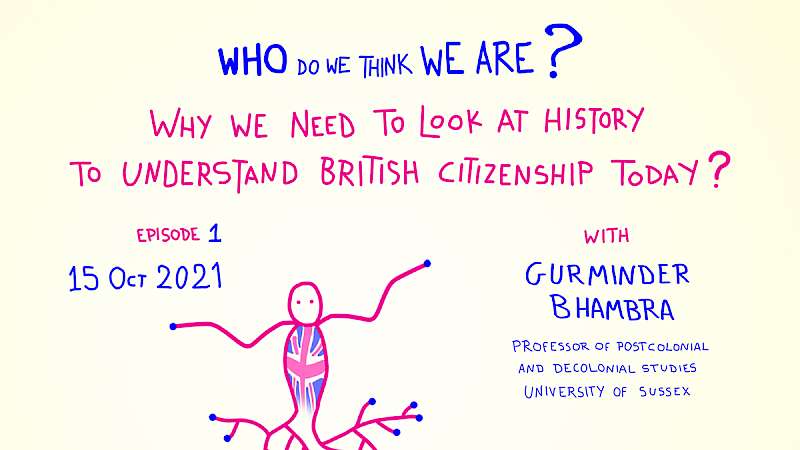

Michaela: Welcome to “Who do we think we are?”, a podcast exploring some of the forgotten stories of British citizenship.

I am your host, Michaela Benson, a sociologist specialising in citizenship, migration and belonging, and professor in public sociology at Lancaster University.

Join me over the course of the series as I debunk the taken-for-granted understandings of citizenship and explore how thinking differently about citizenship helps us to make sense of some of the most pressing issues of our times.

Gurminder: I was talking to my dad at one point about these sorts of issues, and he brought out all these old passports because he keeps everything—his old passports, my grandfather’s old passports—and they were all passports which indicated that they were British citizens.

And it was like “Oh” actually I grew up thinking I was a migrant because that is what school told me, that’s what TV told me, that’s what my friends told me, that I was a migrant.

Why? Because I was darker.

And yet all the documentation is that my family were always British, and I don’t say that for any reason apart from saying that we have to understand our history to understand our present, and if we don’t understand that people within Britain who are not white are nonetheless citizens, then we misunderstand inequalities as produced by a particular phenomenon, as opposed to by other ones, and therefore we don’t address these issues sufficiently.

Michaela: That was my guest on today’s episode, Gurminder Bhambra, Professor of Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies at the University of Sussex, with a real-life example of how taken-for-granted understandings of citizenship that map it onto the nation-state, have a very recent history.

But before we hear more from her, I want to share with you a little of my own family story.

My maternal grandparents were born 9,730 miles apart: my grandmother in Hong Kong, the third daughter of the third generation of a Muslim family, and my grandfather just a few short miles from Stonehenge.

Their early lives would be very different to one another.

Children during the Second World War, my grandmother would live through the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong while my grandfather, just too young to see active service during the war, attended grammar school.

Despite these differences in their early lives, what they shared in common through their birth in different parts of the British empire was a status: born in 1928 they were both British subjects.

The world has changed a lot since then.

Britain is no longer an empire—at least not in name—and those born in Hong Kong today, a special administrative region of China since 1997, would have a very different legal status—as Chinese citizens—to those born in Wiltshire—as British citizens.

But this is not simply a story of how the world has been reordered since then and the emergence of the nation-state as the predominant political unit.

It is more complex than that.

It is the story of how the status of those born British subjects would radically change over the course of my grandparents’ lifetimes, over the course of the 20th century and what this would mean for their lives.

It is a story that lays the foundation for understanding contemporary issues relating to citizenship and migration in Britain, including the Windrush deportation scandal, Brexit and the EU settlement scheme, and Britain’s continuing obligations and responsibilities to the people of Hong Kong.

1928 is just over ninety years ago—an admittedly long human lifetime—but it’s a reminder of how much things have changed in a relatively short period of time.

Citizenship, with its relationship to identity and belonging, is often assumed to have a longer history than it does; it’s assumed to be more stable over that period of time.

But, as we’ll be discussing in today’s episode, this is a misconception.

We’ll be hearing more from Gurminder about how recognising the complex history of British citizenship, and how it developed over a period of time, might help us to think differently about contemporary questions of migration, citizenship and belonging in Britain.

Keep listening to find out more.

For today’s episode, I asked George Kalivis, the researcher for the podcast, to go back into the archives to find out how the Commonwealth Immigration Bill of 1962 was announced. Let’s hear more from him about what he found.

George: Announcing the second reading of the Commonwealth Immigrants Bill in the House of Commons in November 1961, The Times used the headline “Immigrants Bill: presented as necessary but distasteful”.

The article starts with comments from the Home Secretary, Rab Butler, Conservative Party MP, explaining the grounds on which the Government had reluctantly approached parliament to request they might be granted the power to control immigration from the Commonwealth.

Let me read a small extract:

“Throughout the continuous evolution of the Commonwealth, the citizens of member states had been free to come to Britain and stay as long as they like.

“The justification for the control, which was included in the Bill, was that a sizable part of the entire population of the earth was entitled to come and stay in this already densely populated country—a proportion amount to one-quarter of the population of the globe.

“At the time of the bill, Mr Butler stressed that there were no factors visible to lead the Government to expect a reversal, or even a modification, of the immigration trend.

“The Government did not believe, therefore, after very serious consideration, that any country could permit the indefinite continuance of virtually limitless immigration.

“A new factor in the last few years or so”, he continued, “is immigration from other parts of the Commonwealth, notably the West Indies, India, Pakistan, and Cyprus, and to a lesser extent, from Africa, from Aden and from Hong Kong.”

Now, it's remarkable how familiar this narrative seems in today's context.

I thought this could be useful to think about.

Michaela: I think that George makes a really good point there, about the seeming continuity in the way those issues were spoken about back in the 1960s and some of the things that we see today.

But, to provide a little bit more context to what was going on here, I thought we talk a little bit about subjecthood.

What exactly is a “British subject”?

Whether you already know the answer may depend on how old you are!

For me, it seems like an artefact of a time long gone.

So, I was surprised in a recent Zoom meeting, where I had been explaining my research, to be confronted by a man in his 60s who explained that in school he had been taught that he was a British subject, and he’d never really thought of himself as anything else.

I already spoke to you about how this was a status that both my grandparents held despite being born on opposite sides of the world.

Quite simply, this was the status given to all those born in the British Empire.

It was written into law through the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act in 1914.

And we have to remember that the British World looked quite different at the time.

The empire was spread across six continents, with the result that British subjects were dispersed all over the world.

Subjecthood was the common-law principle where allegiance to the Monarch and their political institutions resulted in protections from the state towards their subjects.

But the important thing that I just want you to remember here is that this was a common status for all of those across the empire.

Now, before we hear from Gurminder, I just want to talk a little about the relationship between citizenship and the nation-state.

What’s happened between 1928 and today is a long process by which Britain decolonised.

And I'm using that phrase here simply to talk about how Britain transformed from an Empire to a nation-state, as first its dominions and then some of its colonies demanded independence.

These struggles for independence and the right to self-determination necessarily included the development of local citizenships.

Now, this is really important because at that time citizenship did not exist in British law.

As I stated before, everybody across the British Empire had a status as subjects and, so, in many ways by the time Britain first includes citizenship in its laws—which it does through the British Nationality Act of 1948—it was a bit of a latecomer to the party.

But let's think for a minute about what citizenship does within the context of the nation-state.

What this does is it draws a line around who is a member of that political community, simply, who politicians and other people in power thinks constitutes the community in whose interest they act.

In other words, it names whom the Government have obligations and commitments towards.

But I want you to just hold that in your mind as we think a little bit further about the story of British citizenship with Gurminder.

I started by asking her what she thought was wrong with the commonplace understandings about who has the rights as citizens in the UK today.

Gurminder: That, in a sense, can’t be understood out of the frame through which we understand what Britain is and so, if we are thinking about citizenship, citizenship is understood as something that emerged with the development of the modern nation-state.

Just to give some background to that, the first time that Britain established a formal understanding of citizenship wasn’t until 1948, and it only did it then because its dominions and its former colonies, which were now becoming independent, were all establishing forms of citizenship.

So, India becomes independent in 1947 and from the outset establishes a form of citizenship or what it means to be a citizen of India.

Britain at that stage doesn’t have citizenship defined, in particular ways, and so it is not until the British Nationality Act of 1948 that Britain legislates for the first time who constitutes a citizen.

And interestingly, the very first articulation of this acknowledges citizens as belonging to the imperial state, because what it sets out is that there are two main forms of citizenship: one is that you are a citizen of the UK and its colonies—and that is incredibly important there, “of the UK and its colonies”.

So, it is a common shared citizenship, there’s no distinction made between whether you live in the UK or you live in the colonies; you share a common citizenship.

And then, the second form of citizenship is Commonwealth citizens, and that’s given to anybody who lives in a country that is now part of the Commonwealth and was formerly part of the British Empire.

Michaela: I think that’s really really helpful as a way of explaining things and the kind of, you know, there’s always a danger, isn’t there, of kind of thinking with questions of citizenship as they emerge now, as they are territorialised now, and then thinking back to 1948 and forgetting that in 1948 citizenship was about being citizen of an Empire where there was no real expectation of anyone moving, and where Britain had this vast power as well, through its imperial state.

How does the repositioning of a kind of contemporary understandings of migration and citizenship within Britain... How does repositioning those in the imperial history and decolonisation change our taken-for-granted understandings, I suppose?

Gurminder: When we start thinking about questions of citizenship, and thinking about questions of belonging that are often associated with citizenship, we have an implicit understanding that citizenship is linked to the nation and, therefore, those who belong to the nation belong—have the right of citizens—and we fail to understand that the imperial state is what organised citizenship and therefore belonging is a racialised category that has been laid on top of our understandings of citizenship, but we use citizenship as an abstract category and not recognise that.

What is so interesting about citizenship is how contemporary a phenomenon it is, in many ways.

So, things that we think have always existed such as the passport, or borders, haven’t existed for that long.

There is a wonderful book by Radhika Mongia setting out the very emergence of the passports and the idea of borders, and how often what was being policed was the entry of people from the colonies coming into metropoles; it wasn’t something that was required for people who were moving from the heart of Empire to the colonies.

And so, citizenship is something that emerges in the mid to late 20th century as a category by way of which to stop people moving.

We often think about this idea of passports as if that’s what enables us to move; actually, it was about stopping people moving.

And one of the things that I find so fascinating, and the debates around British citizenship, is that from this expanse, you know, people might ask “Why on earth did Britain give citizenship to around 800m people?”—because that’s who was technically eligible for it in 1948; because in giving the citizenship to everybody within the Empire, that’s how many people would have had the rights to travel to Britain, to live in Britain, to work in Britain, and in all other parts of Empire as well.

Now, when talked about this, people have said “Why on earth did Britain do this?”, and it’s like, well, what you have to remember is that in 1948 the direction of travel of migration was still very much from Britain to the rest of the world, it wasn’t from other parts of the world to Britain, that is only a phenomenon that began to occur in the ‘50s and ‘60s, and as soon as you began to have people from the darker parts of Empire coming to Britain that is the point at which there are immediately debates in Parliament and elsewhere about what could be done to stop coloured migration.

They weren’t interested in stopping people moving from places like Canada, New Zealand and Australia to Britain.

They were interested in stopping people from the West Indies, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, coming to Britain.

But it was incredibly difficult to create barriers to people from some parts of the Commonwealth versus other parts of the Commonwealth, so they tried all sorts of ways of doing this.

And the Commonwealth Immigration Acts that you get in the 1960s and ‘70s are instances of gradually taking rights away from people, not on the basis of race, but on the basis of geography, which stands in for race and is something that comes to be explicitly racialised over time.

Michaela: I think that one of the things that is really clear in your work on citizenship is that you’ve argued that neglecting the kind of imperial histories, in the construction of who is a citizen and who is a migrant, translates into what we could see as a neglect of a polity as structured by race.

Could you explain that in a little bit more detail?

Gurminder: I mean, in terms of thinking about the way in which these things are understood in the present, I think one of the key aspects, that is completely misunderstood, is the fact that people who are called 2nd and 3rd generation migrants are not migrants, but are actually citizens.

And that misunderstanding emerges around the fact of the extent to which we had an understanding of citizenship as belonging to the nation, and the nation is understood as white, and therefore anybody who is not white is obviously not a citizen but a migrant.

And trying to explain to people that actually, as a consequence of the British Empire, citizenship was given to people who weren’t white, and they were citizens, and they were citizens with all the same rights and responsibilities of white British people, and that when many people moved from different parts of the Empire to Britain they weren’t crossing borders in their movements, they were simply travelling within an imperial polity.

And, to my mind, to be a migrant you have to cross a political border, you have got to move from one polity to another and that’s what constitutes you as a migrant.

If you move within the circuits of Empire, it is not clear to me why people ought to be understood as migrants, as incoming from another polity, because they are not.

One of the things that we often think about when we think about Britain is that Britain is its own particular entity, and the racial inequality that structures Britain is related somehow to people who are understood as migrants who come into the polity, and they come in either as invited guest workers or to labour or sometimes not as invited at all, but are nonetheless here.

So, their presence here is presented as somehow irregular; even the ones who come through regular means are presented as coming from the outside and, therefore, the differences and experience that they might have in terms of access to jobs, to opportunities and so on is seen to be justified because they are not part of the nation, they are not part of the history of belonging to the nation.

And even over the last few years, we have seen how so many elections and other political moments have been organised around this idea of who ought to be the legitimate object of public policy in this country.

And whenever racial inequalities are raised, one of the things that sometimes gets presented back is “Well yes that’s important, but we need to look after our citizens”; and so there is a distinction made between our citizens and others.

My argument is partly that many of those who are considered as other were actually part of the polity and belong to the history of Empire, and therefore ought not to be treated as outsiders who are coming in requesting stuff, but actually are legitimate beneficiaries of the rights, opportunities and benefits of Britain as currently articulated.

Michaela: I think that is really important in terms of reframing that particular narrative about welfare recipients and who that money is for, and as you say, who is a legitimate object of public policy.

And I know that that’s part of a bigger project that you have been working on as well.

I mean, what would it do—again this might be a self-evident question—but what does it do to reposition those darker-skinned citizens as full members of the polity?

Gurminder: Well, it might enable us to just to focus on policies that address the socio-economic inequalities that structure our society.

To the extent that there’s presented to be a concern with issues of class in the present, it is too often racialised as a concern with the white working class and, to my mind, there’s a misunderstanding of who constitutes the working class in Britain if one racialises it to think only of the white working class.

The working class in Britain is multi-cultural, it’s multi-ethnic and it includes people who aren’t citizens of Britain because of the extent of migrant labour that is needed to keep the economy going in particular sorts of ways.

And so in that sense, if we were to recognise people as constituting society we were to recognise that we were both empirically and descriptively multi-cultural, then we wouldn’t need to necessarily have our focus on those issues but could think about what needs to be done that would make life better for all of us.

Michaela: I think that Gurminder puts forward a really powerful argument that challenges modern-day understandings of who is a citizen and who is a migrant.

But her argument goes a little bit further than that.

She highlights that remembering this history by which people who we might now consider as outside the boundaries of the political community, were once members of that community when it existed in its imperial form, means also recognising that they equally contributed towards its wealth and prosperity, and yet, as that community shrank to the size of the nation—when these goods were redistributed through, for example, welfare—they found themselves outside that community.

Remembering that citizenship is a contemporary phenomenon gives us a different point of entry into understanding questions of belonging and identity in Britain, and how these have been mobilised in arguments about who should have access to public resource and social entitlements.

I’ll pop some suggestions into the episode notes for further resources where you can find out more about this, including some fantastic pieces by Gurminder.

But let’s have a quick think about why this matters in the present day?

Just think about the Windrush Deportation Scandal; or questions in the last year or so about what Britain should do for the Hong Kongers.

If we go back to the 1920s and ‘30s, those from Britain’s colonies and territories in the Caribbean and Southeast Asia shared a common status with those born in the UK.

All these “British subjects” were able to move freely through the Empire and Commonwealth, at least in theory.

As I explained in the opening to my episode, this meant that my grandmother, born in Hong Kong, and my grandfather, born in Wiltshire, shared a status as British subjects.

And yet, over the course of their lifetimes, changes would be introduced in British immigration and nationality law that would mean that those born in colonial Hong Kong would eventually have a fundamentally different legal status to those born in the UK.

We’ll be exploring all this and more in coming episodes.

END OF TRANSCRIPT

Did you know that the current definition of British citizenship is only 40 years old? Who do we think we are? starts its exploration of British citizenship by looking at the history of British citizenship, and how remembering that the question of who counts as British has changed alongside shifts in Britain’s position in the world might make us think again about these questions and their consequences in the present-day.

In this episode, host Michaela Benson, a sociologist specialising in questions of citizenship and migration, draws on her family history to bring the story of British citizenship in the second half of the twentieth century to life and explores British subjecthood, a precursor to citizenship. Podcast researcher George Kalivis goes back into the archive to explore the 1961 Immigration Bill and the measures that this introduced. They are joined by guest, Gurminder Bhambra, Professor in Postcolonial and Decolonial Studies at the University of Sussex, to talk about how recognising the back story to the development of British citizenship might change the ways that we think about migration, social justice and inequality in Britain today.

In this episode we cover …

- The short history of British citizenship as we know it

- The introduction of immigration controls for Citizens of the UK and Colonies

- Why history matters for making sense of the inequalities at the heart of Britain’s contemporary citizenship-migration regime

Citizenship is something that emerges in the mid to late 20th century as a category by way of which to stop people moving. We often think about this idea of passports as if that’s what enables us to move; actually, it was about stopping people moving.

— Gurminder Bhambra

Where can you find out more about the topics in today’s episode?

You can find out more about Gurminder’s research on her website (which includes links to freely-accessible copies of many of her published works) and follow her on Twitter @GKBhambra

You can read Michaela’s full interview with Gurminder in The Sociological Review Magazine

Gurminder also mentioned Radhika Mongia’s 2018 book Indian Migration and Empire. To get a bit more of a flavour of the book and its contents, you can visit The Disorder of Things Blog, who have hosted a symposium on this work.

Call to action

You can subscribe to the podcast on all major podcasting platforms or through our RSS Feed.

To find out more about Who do we think we are?, including news, events and resources, visit our blog and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.